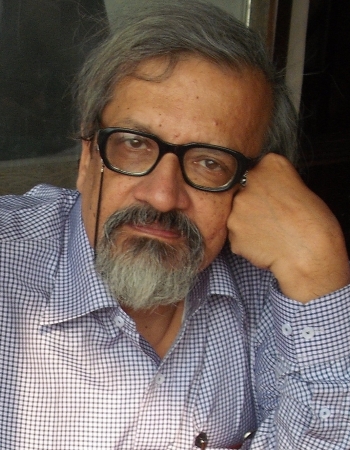

Hari Vasudevan : In remembrance

Do svidaniya До свидания (Goodbye, Till We Meet Again)

This website is dedicated to Prof. Hari Sankar Vasudevan (February 15, 1952-May 10, 2020), an eminent teacher, public intellectual, and historian of Tsarist, Soviet and post-Soviet Russia, Eurasia and Indo-Russian relations. Having studied in India, Kenya and the United Kingdom (where he completed his Tripos in 1973 and PhD in 1978 from Cambridge University), his career was built at the Department of History, Calcutta University, where he became Professor in 1999 and taught for four decades. From the time he joined as a Lecturer in 1978 till his retirement in 2017 and thereafter, his teaching ranged from European and Russian history to international relations and courses on the history of industrialization, comparative economic development and planning in contemporary India.

During the 1990s and 2000s, Prof. Vasudevan was associated with various other institutions and initiatives such as the Russian Archives Project of the Asiatic Society, Calcutta; the Central Asia programme at Jamia Millia Islamia University (JMI), New Delhi, where he was Professor of Central Asian Studies, and the Director of the Third Word Academy (from 2002-2005); and the new textbook projects of the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), New Delhi. He researched and lectured at a number of foreign institutions such as the Academy of Sciences (Russia), Kiev University (Ukraine), Maison de Sciences de l’ Homme (France), Uppsala University (Sweden), Cornell University (USA), King’s College (UK), Yunnan Normal University (China) and Dagon University (Myanmar).

A skilled administrator and institution builder, Prof. Vasudevan served as Director of the Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies (MAKIAS), Kolkata, from 2007 to 2011, and was alongside affiliated with several other academic and governmental institutions in New Delhi and Kolkata. For several years, he was also closely associated with teaching courses at the Institute for Civil Service Aspirants, Calcutta. Post retirement, he became UGC Emeritus Professor at Department of History, Calcutta University, after which he took up in September 2019 the position of Visiting Distinguished Professor, Observer Research Foundation, and was President, Institute of Development Studies, Kolkata, from July 2018 to May 2020.

Just as the French Revolution has come to be identified with the Terror and Napoleonic despotism, and the Chinese Revolution with the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, the Russian Revolution has accumulated associations with Stalin’s Russia, the Brezhnev bureaucracy and forces that led to the collapse of the USSR under Mikhail Gorbachev. The moment of revolution itself is linked to the Civil War. The traumas have been brilliantly outlined by Boris Pasternak, its uncertain origins more idiosyncratically by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his Red Wheel corpus. Complex aspects of the original event are forgotten in much of this. Not least among the casualties are social aspirations and a sense of hope, as the revolutionary momentum gathered from a pivotal incident, the Bolshevik coup of November 6, and an overwhelming sense of transition, recognised locally and globally...

Hari Vasudevan, “On the Russian Revolution’s Centenary: Will History Defeat Rhetoric?”, The Wire, November 1, 2017.

The problem of the migrant’s hunger may, correctly, easily be put down to an errant state allowing want against a background of abundance, a situation so brilliantly depicted in Satyajit Ray's Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder), 1973, or to the misadventure of ignorant informal labour that is a victim of political machinations. But, let us make no mistake about both. In today's India, they are the outcome of something that reveals a terrifying truth: a social innocence about genuine starvation and want that limits public capacity to make demands of the state; insensitivity to the message in the Malayalam language hit film Ustad Hotel (2012) that relish for food is empty if it ignores the plight of those unable to savour it. This is an appalling comment on where India’s Republic has arrived, when much of its original project was to deal with these very problems.

Hari Vasudevan, reflecting on hunger, starvation and the migrant labour crisis during India’s lockdown: “Food is a Necessity, So is Making it Available”, Newsclick, April 22, 2020.